Return

|

Ref ID: 1AP2024/8878 | Posted On: 08-09-2024 | Updated on: 08-09-2024

|

|

The Greatest Love Story That Never Started: Tereza and Davit

Long before I encountered the details of this story, I had heard about it, repeatedly. It was often described as “the greatest love story ever told” or “a romance that began at the worst possible moment.” Some even labeled it “a love story that never ended.” Yet, the full narrative was never properly disclosed, and each time I was left with only fragments I had to piece together.

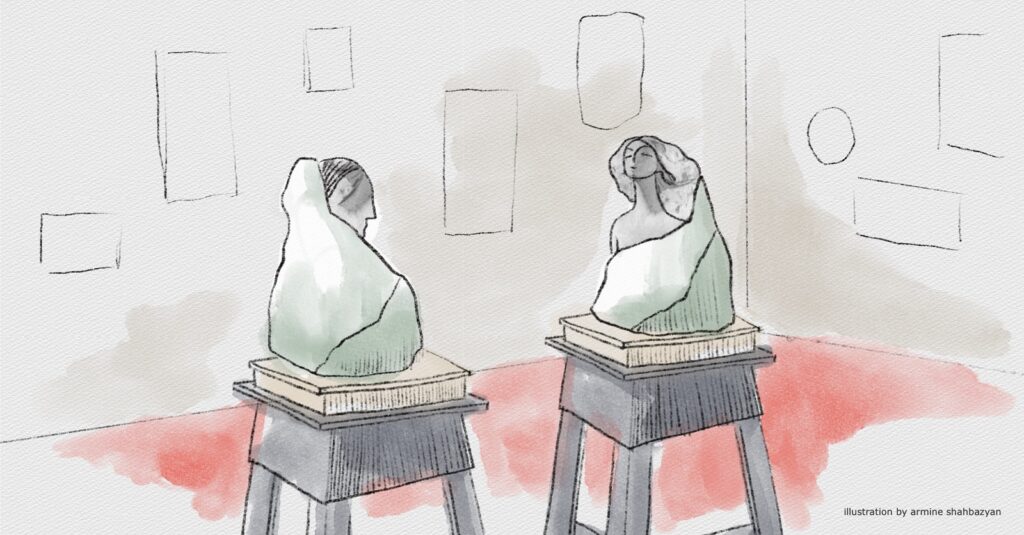

The story is set against the backdrop of World War II, and revolves around two sculptors. One was Davit Metreveli, a Georgian, and the other was Tereza Mirzoyan, an Armenian—one of the few women working in the field at the time. Mirzoyan’s legacy endures to this day through her monumental work and the countless students she mentored through art and life. That’s all I knew: two people, likely separated by war. I never knew if they were reunited or found a happy ending.

It wasn’t until early July that I was reminded of this story again, this time by a Russian journalist. They were intrigued by it and surprised that no one had ever thought of turning it into another “Titanic” or some other great love story that breaks all barriers.

On August 24, I was on my way to the studio where Mirzoyan’s works are now stored. The studio, the oldest on this street, once belonged to Tereza’s former father-in-law and is now owned by her family. Across the street, I could see Tereza’s “Love Me, Love Me Not”, a statue standing 1.6 meters high. In the 1990s, the original copper work was stolen, and this new version in bronze was recreated by her daughter, Anush.

During our student years, we used to bring flowers and place them at the feet of this statue when our relationships faced tough moments. I have no idea who came up with that tradition, but it really did soothe our broken hearts.

I crossed the street and walked into the building.

On the top floor, the door opened, and a beautiful woman greeted me. It was Tereza’s daughter, painter Anush Arakelyan. Her sharp-edged eyes resembled details from Sumerian relief sculptures, yet they were just part of her body––inherited from ancestors whose eyes probably saved or played an important role in their lives. We rarely consider that we carry the eyes, smiles, and gestures of those who came before us––features that helped them survive, carry on, and thrive.

Anush seemed totally aware of this, and now she was going to share something passed down to her––her mother’s story.

She guided me through the studio’s works. The wide, bright, modestly furnished room looked as if nothing had changed since Tereza`s presence, welcoming me as if I were a frequent guest.

As Anush and I walked through the room, her mother’s works shared the space with her own paintings, creating a sense of ongoing dialogue between the two.

Anush briefly disappeared into the farthest corner of the room, returning with two books: a large catalog of her mother’s work and a slender volume of her short stories.

While I browsed through these books, she made coffee, and we sat at the round table.

“If you don’t mind I’ll read it aloud to not miss any important detail,” she said, taking the thin book and then started reading, “I remember this story from early childhood.” She paused.

“Mom used to tell this story very often, and each time I listened, I would hold my breath as if it was the first time. It was the 1940s. Mom started to study sculpture at the Academy of Arts in Tbilisi. Later, their small class, mainly consisting of men, was joined by a newcomer––someone a bit older with a military background. His name was Davit Metreveli, whom students called Dodic. He was a tall, handsome, interesting, and talented man, who caught mom’s attention. And he fell in love with mom right away, at first glance, just like many others at that time. That’s how their story started.”

Anush’s voice carried a subtle sadness as she continued.

“It was 1941. The war started. All the young men from mom’s class were sent to war, including Dodic.” Anush paused, raised her eyes, and added, “Basically that year the entire class was sent to war because all were men except my mom. The academy even thought about eliminating this sculpture class, as they didn`t see a reason to keep it for just one person—my mom. But, of course, that didn’t happen, and my mom graduated. It’s really interesting that she was all alone there.”

Anush resumed reading. I flipped through the catalog, listening to her story while looking through the pages. There was a photo of Tereza, radiant in a black dress adorned with large statement earrings. Near the photo, I spotted a familiar surname—“Metreveli”—and began reading. It was a passage from her autobiography that almost synced with what I was hearing at that moment. It read:

“We were supposed to be sketching at the zoo that day, but he showed up without his sketchbook, there to bid farewell instead. Initially, we didn’t take this war seriously, as we had experienced a war before with Finland which only lasted three months. He asked me to wait for him for that period—three months. We didn’t believe the war would last longer than that…”

Anush carried on reading.

“Mom was heartbroken but hoped for his return. On the day of departure, she gave him a silver spoon she’d had since birth for protection. Their last meeting was at the station.

“Mom was so upset that wanted to wear a black dress that day, but her friends told her off, saying it was bad luck. Instead, she chose a new red dress, which suited her very well. Dodic was taken aback by her beauty and asked her to wear that same red dress when he returned.

“In anticipation, the days stretched painfully long. There was hardly any news from Dodic. Once, he sent money to my mother and asked her to buy herself a present. She bought a wonderful pearl necklace and earrings. After that, Dodic disappeared for a while. No letters came from him.

“When mom’s friends found out that she bought pearls for herself, they warned her that it was a very bad sign—pearls bring tears. That day, mom took a hammer and broke the necklace and earrings into tiny little pieces.”

At that very moment, my earring slipped off—just a coincidence. Fortunately, it landed softly on my dress, without making a sound that might distract Anush or lend a haunting air to the story.

“I don’t know what was going on in her heart,” continued Anush, “but the next day she received news from Dodic. In his letter, he revealed that they were surrounded by the enemy. However, he wrote that all was fine and the bad times were already behind them.

“A year later, Dodic disappeared again. Rumors had it that his troops were captured in Kharkiv. It was 1942, and ‘captured’ meant ‘executed’.

“Soon the war ended, and expectations and hopes waned as well. It became clear that fate had separated them forever.” Anush paused for a moment and looked at me.

I looked at her, slightly lost, hoping that this wasn’t the final part of this story. But there were a few more pages in Anush’s story. It wasn’t over yet! Anush continued.

“A few years later, my mother moved to Yerevan. She started teaching at the Art College, and then at the Art and Theater Institute. She became a member of the Artists’ Union and got married. Life went on.”

As Anush’s voice deepened with intrigue, Tereza’s biography drew me in once more. Anush revealed that years later, she heard from a former classmate who had encountered Davit in London. He was alive and well, though he had cut all ties with his family to protect them. As a former prisoner of war, he had to sever all connections to his past to avoid exile. Once again, the story seemed to reach a dead end, with little hope that Tereza and Davit would ever reunite.

But then, Anush began a new passage. “Twenty-five years later,” she started, her voice as anxious as if she was reading this story for the first time “a group of artists gathered for a trip…to London.”

“And mom was among them. It was 1965.

“They’re in London, the Embassy Hotel. Mother sits by the phone, takes a thick telephone book, and carefully slides her fingers over the letter M. She finds Metreveli and dials the number…” Anush pauses and explains, “By the way, Metreveli is a very rare surname, even for Georgians.” Then she continues.

“…A woman answers.” Anush pauses, allowing me to cycle through all shades of anger and possible identities of this woman. No, not a wife for sure! “Mom asks for David…”

Silence for a second, then a familiar male voice greets her.

“Dodic?”

“Yes, who is this?!”

“It’s Tereza…”

“…Where are you?”

“I’m in London, at the Embassy Hotel.”

“… I`m coming!”

Now I understand why Anush sounds anxious. It’s one of those stories you know by heart, yet you always hope the plot might change someday.

Anush continues, explaining, “Metreveli was a rare surname, so mom found him easily. But ‘Embassy’ wasn’t such a rare name for a hotel—in fact, it was a chain of hotels—so it took a while until he found mom.” Then she resumes reading.

Meanwhile, my eyes slid through Tereza’s autobiography: “We met. He joined our group on a guided tour of the British Museum and later invited my friends and me to his home. His close friend, a Georgian living in Spain, was also invited. As I walked into his house, his friend gave me a long gaze and asked, ‘What color is your dress?’ I responded quite nonchalantly, ‘Red.’ I had totally forgotten about our past exchange.”

“It became clear that conversations about mom were frequent between the two friends,” continued Anush. “They went to the nearest cafe. Dodic was very nervous; his hands were shaking when he tried to light a cigarette. His friend soon left them alone, citing business.”

For a moment, I felt as if I were hearing voices of two women, simultaneously telling the same story that had remained present throughout their lives.

So Davit was alive! He was miraculously saved by his rare surname.

On the day of Davit’s execution, one of the German commanders rushed to stop it after hearing a familiar surname: “Metreveli”. It turned out to be David’s cousin, an orphan raised by his father. He helped David and sent him to Germany. Later, David himself relocated to London, where he restored paintings to make a living. The woman replying on the phone was a Ukrainian nurse who had also ended up in London with her child. She was a single mom and David’s neighbor. David felt connected to the boy and chose to adopt him and marry his mom, though with a special condition: they would keep a respectful distance because there was already a woman he loved.

“He suggested that I stay, but I replied that I was happily married,” Tereza wrote in her autobiography. This was the part where I hoped for some continuation, but I couldn’t see anything.

“Mom said it despite being divorced at the time,” continued Anush. “I often asked her later why she didn’t stay, and tried to describe the whole allure of London life with a loved one.” She said this while reading, but pronounced it as if it were a question she’d once frequently asked. Then she continued, now speaking to me, as the story had apparently ended.

“You know, in the 1990s, mom used to stay up late preparing dough, and then wake up very early to bake. She was making pishkis—little donuts—for her students, because these kids sometimes came from neighboring cities or regions and were all hungry. Well, you know what the 1990s were like. Mom baked the pishkis so they’d have a little energy during class to sculpt and work. She never bragged or showed any sign of regret. I admire her for that. She was such a strong woman and always helped others, even when she should have been thinking about herself. Even in this case, she cared more about that woman from Dodic’s story than about their reunion. She always remembered how alarmed and scared this woman looked when mom was there. But mom couldn’t harm anyone.”

While Anush continued, I was thrown into the colorful images of London in the 1960s. When Tereza met Davit, in 1966, the Beatles’ epic “Revolver” album was out with Eleanor Rigby, a monumental work about all the lonely people and destinies they share. In the 1960s, TVs switched from black and white to color and life offered more shades, more freedom. In stark contrast, the Armenian 1990s emerge as an era of seemingly endless darkness, with a biting cold that seeps into your bones, and the scent of cracked wood lingering in your hair and breath. Two vastly different realities of life, each etched in the memory in its own way. But it’s always easy to accept hardships, when you know it’s your choice and not your fate.

Tereza penned these words in 2002 at the age of 80. Of the 2,855 words she used to chronicle her eight decades of life and career, 719 were devoted to Davit, whom she remembered as her one true love.

I set out in search of a great love story that never ended, but perhaps I discovered a story that never truly began.

Perhaps stories without beginnings are destined to live forever in our imagination, never truly ending. Maybe they exist to remind us that beyond our daily routines, something far greater awaits, ready to unfold if we commit to it. While I’m uncertain about these musings, I know one thing for sure: I’ll spend the evening searching for the rare surname Metreveli online, examining each face the search engine reveals, wondering who inherited Tereza’s silver spoon and the other half of this story.

Anush’s story concluded with gratitude for her mother’s choices, while Tereza’s autobiography summed up her love story with this poignant sentence:

“We never met again. Yet his presence lingers in my life, even the sculpture stand I continue to use was crafted by his own hands.”

Author’s Note:

I am grateful to Ilya Bazhan, an amazing journalist and founder of Bazhan media, for sharing this story with me and to all the women of Mirzoyan family for their time, and their openness.